Dispute Resolution HotlineJanuary 18, 2017 Delhi HC adds to uncertainty over applicability of the Arbitration & Conciliation (Amendment) Act 2015

INTRODUCTIONThe applicability of the amendments to Indian Arbitration & Conciliation Act, 1996 (“Act”) have been the bone of contention in several cases. Section 261 of the Arbitration & Conciliation (Amendment) Act 2015 (“Amendment Act”) clarified that the amendment will be prospectively applicable. However, the Madras2 and Calcutta High Courts3 have previously held that the prospective applicability of the Amendment Act would be limited to ‘arbitral proceedings’ and not to ‘court proceedings’. The Bombay High Court4 took a slightly different view: wherein it was held that “it makes no difference if the application under Section 34 filed by the award-debtor was prior to 23rd October, 2015” (discussed later). Similar issue came up for consideration before the Delhi High Court (“Court”) in the decision of Ardee Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd. (“Appellant”) v. Anuradha Bhatia (“Respondent”)5 with Ardee Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd. (“Appellant”) v. Yashpal & Sons (“Respondents”)6. FACTS AND ARGUMENTS ADVANCEDA final award was made in favour of the Respondents on 13 October 2015, which was challenged under Section 34 of the Act on 4 January 2016. The Single Judge issued notice on Respondents challenge petition under Section 34 of the Act, subject to deposit of a sum of Rs. 2.70 crores. Subsequently, an appeal was filed against Single Judge’s order before the Division Bench. The primary contention was the applicability of the Amendment Act and whether merely filing a challenge under Section 34 of the Act would lead to an automatic stay on the enforcement proceedings. Arguments by the Appellant The Appellant contended that the petitions under Section 34 of the Act would be governed by the un-amended provisions of, inter alia, Sections 34 and 36, therefore, entitled to the right of an automatic stay on the filing of the petitions under Section 34 of the said Act. The basic premise of the Appellant for adopting a prospective interpretation of Section 26 of the Amendment Act was that the amendment tends to take away vested rights (substantive rights) of the party challenging the award, to have an automatic stay on the award. Arguments by the Respondents The Respondents argued that the amended provisions would apply to court proceedings and, therefore, there would be no question of any automatic stay and that the order made by the Single Judge was within his powers. The Respondents relied on the case of Thyssen Stahlunion Gmbh v. Steel Authority of India Limited7 (“Thyssen”) to interpret the difference between “to arbitral proceedings” and “in relation to arbitral proceedings” in Section 26, as the latter referring to not only proceedings pending before the court but also proceedings emanating from or related to such arbitral proceedings like court proceedings etc. related to the arbitration. It was also argued that the amendment leading to disentitlement of having an automatic stay subsequent to a challenge of an award, does not divest a party’s right to challenge, rather it only introduces minor changes to such an interim relief, which is not a vested or accrued substantive right. JUDGMENTOn examining the contentions put forth by the parties and the contents of Section 26 of the Amendment Act, the Court came to a finding that the date of commencement of the Amending Act, that is, 23 October 2015, is what separates Section 26 into two parts: (i) the amendments shall not apply “to arbitral proceedings” commenced before the commencement of the Amendment Act, and (ii) the amendments shall apply “in relation to arbitral proceedings” commenced on or after the commencement of the Amendment Act. The Court referred to the Thyssen judgment where the Supreme Court had observed that the right to enforce an award “when arbitral proceedings commenced under the old Act under that very Act was certainly an accrued right” and, “there is no necessity that legal proceedings must be pending when the new Act comes into force.” The Court construed this as equivalent to arbitral proceedings commenced prior to 23 October 2015, and an award being made prior to 23 October 2015 but challenge being made post-amendments, which is the present case. The Court accepted that the second part of Section 26 covers both, proceedings before the arbitral tribunal as well as court proceedings in relation thereto or connected therewith. However, the Court opined that if the applicability of the amendments to both parts are treated differently, it would lead to serious anomalies. This is primarily because of the fact that there have been amendments to Section 9 as well as Section 17 of Act8 and, in respect of arbitral proceedings commenced prior to 23 October 2015, the amended provisions would apply to proceedings under Section 9 of the Act, but not to Section 17 thereof. Thus, the expression “to arbitral proceedings” should be given the same expansive meaning as “in relation to arbitral proceedings” so that “all” arbitral proceedings (including court proceedings) that commenced prior to 23 October 2015 are governed by the un-amended provisions. To further illustrate all the arbitral proceedings, which commenced in accordance with the provisions of Section 21 of the Act prior to 23 October 2015, the Court referred to the following graphical representation:

Based on this representation, the Court concluded that if the first part of Section 26 applies only to arbitral proceedings in the sense of proceedings before arbitral tribunals and not to court proceedings, then, it is obvious that Section 26 is silent on second and third categories of cases. Thus, no contrary intention of retrospectivity could be inferred upon a reading of Section 26 of the Amending Act. The Court, expanded the scope of the right to enforce an award as an accrued right to be inclusive of the negative right of the award-debtor to not have the award enforced. Thus, on considering that the right to have an automatic stay on the enforcement of the award has ceased, pursuant to the amendments, the Court concluded that these amendments are to be treated as prospective in operation. ANALYSIS:This judgment clearly conflicts with the earlier observations of the Madras High Court9 and the Calcutta High Court,10 wherein it was clarified that ‘arbitral proceedings’ do not include ‘court proceedings’ and by virtue of Section 26 of the Amendment Act, the amendments would apply to court proceedings but not to arbitral proceedings. Undoubtedly, these judgments rightfully establish the distinction between arbitral proceedings and proceedings emanating from or related to such arbitral proceedings as expressed in Section 26 of the Amendment Act, which has been diluted by the Court in this judgment. The Bombay High Court11 looked into the intention behind the amendments and observed that the amendments to Section 36 sought to balance between the rights and liabilities of the award-holder and the award-debtor, thus prospective in nature. Earlier, a challenge under Section 34 would cast a shadow on the award-holder’s right to enforce the award since an automatic stay would operate. Subsequently, this shadow over the rights of the award-holder was removed, by way of the amendments. Meanwhile, the rights of the award-debtor were kept intact to the extent that interim reliefs can be sought from the court during the pendency of an application of challenge under Section 34. Thus, the Bombay High Court concluded that “removal of such a shadow over the rights of the award-holder cannot be said to be prejudicial to the award-holder.” There is a risk of extension of ‘automatic stay principle’ which was prevalent in the pre-arbitration regime, debated and purposely omitted in the amendments to the Act. This judgment, if followed may defeat the intention of the amended Section 36 of the Act. The decision of the Bombay High Court has been appealed and pending adjudication before Supreme Court of India. Hopefully, the Supreme Court will settle the position on applicability of the Amendment Act and bring the divergent views of various High Courts to an end. – Shweta Sahu, Alipak Banerjee & Vyapak Desai You can direct your queries or comments to the authors 1 Section 26 of the Amendment Act provides that: “Nothing contained in this Act shall apply to the arbitral proceedings commenced, in accordance with the provisions of section 21 of the principal Act, before the commencement of this Act unless the parties otherwise agree but this Act shall apply in relation to arbitral proceedings commenced on or after the date of commencement of this Act.” 2 New Tirupur Area Development Corporation Ltd. v. M/s. Hindustan Construction Co. Ltd A. NO. 7674 of 2016 in O.P. No. 931 of 2015 judgment dated 27 January 2016 (Madras High Court) [click here for our hotline] 3 Tufan Chatterjee v. Rangan Dhar AIR 2016 Cal 213 4 Rendezvous Sports World v. the Board of Control for Cricket in India, 2016 SCC Online Bom 255. 5 2017 SCC Online Del 6402 6 ibid 7 1999 (9) SCC 334. 8 Section 9 deals with the power of the court to grant interim measures, while Section 17 deals with powers of the arbitral tribunal to grant interim measures. 9 New Tirupur Area Development Corporation Ltd. v. M/s. Hindustan Construction Co. Ltd A. NO. 7674 of 2016 in O.P. No. 931 of 2015 judgment dated 27 January 2016 (Madras High Court) 10 Tufan Chatterjee v. Rangan Dhar AIR 2016 Cal 213 11 Rendezvous Sports World v. the Board of Control for Cricket in India, 2016 SCC Online Bom 255 DisclaimerThe contents of this hotline should not be construed as legal opinion. View detailed disclaimer. |

|

- Delhi High Court has held that the amended provisions would not be applicable to ‘court proceedings’ initiated post-amendments, unless they were merely ‘procedural’ and did not affect any ‘accrued right’;

- It has been held that amendments to Sections 34 and 36 of the Act, which pertain to the enforceability of an award, affect the accrued rights of the parties.

- Contrary to earlier decisions, it has been held that a challenge petition filed post amendment would be governed by un-amended Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 so long as arbitration was invoked in the pre-amendment era;

- A challenge to a pre-amendment arbitral award filed post the amendment, would necessarily result in an automatic stay on enforcement of the award;

INTRODUCTION

The applicability of the amendments to Indian Arbitration & Conciliation Act, 1996 (“Act”) have been the bone of contention in several cases. Section 261 of the Arbitration & Conciliation (Amendment) Act 2015 (“Amendment Act”) clarified that the amendment will be prospectively applicable. However, the Madras2 and Calcutta High Courts3 have previously held that the prospective applicability of the Amendment Act would be limited to ‘arbitral proceedings’ and not to ‘court proceedings’. The Bombay High Court4 took a slightly different view: wherein it was held that “it makes no difference if the application under Section 34 filed by the award-debtor was prior to 23rd October, 2015” (discussed later).

Similar issue came up for consideration before the Delhi High Court (“Court”) in the decision of Ardee Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd. (“Appellant”) v. Anuradha Bhatia (“Respondent”)5 with Ardee Infrastructure Pvt. Ltd. (“Appellant”) v. Yashpal & Sons (“Respondents”)6.

FACTS AND ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

A final award was made in favour of the Respondents on 13 October 2015, which was challenged under Section 34 of the Act on 4 January 2016. The Single Judge issued notice on Respondents challenge petition under Section 34 of the Act, subject to deposit of a sum of Rs. 2.70 crores. Subsequently, an appeal was filed against Single Judge’s order before the Division Bench.

The primary contention was the applicability of the Amendment Act and whether merely filing a challenge under Section 34 of the Act would lead to an automatic stay on the enforcement proceedings.

Arguments by the Appellant

The Appellant contended that the petitions under Section 34 of the Act would be governed by the un-amended provisions of, inter alia, Sections 34 and 36, therefore, entitled to the right of an automatic stay on the filing of the petitions under Section 34 of the said Act. The basic premise of the Appellant for adopting a prospective interpretation of Section 26 of the Amendment Act was that the amendment tends to take away vested rights (substantive rights) of the party challenging the award, to have an automatic stay on the award.

Arguments by the Respondents

The Respondents argued that the amended provisions would apply to court proceedings and, therefore, there would be no question of any automatic stay and that the order made by the Single Judge was within his powers. The Respondents relied on the case of Thyssen Stahlunion Gmbh v. Steel Authority of India Limited7 (“Thyssen”) to interpret the difference between “to arbitral proceedings” and “in relation to arbitral proceedings” in Section 26, as the latter referring to not only proceedings pending before the court but also proceedings emanating from or related to such arbitral proceedings like court proceedings etc. related to the arbitration. It was also argued that the amendment leading to disentitlement of having an automatic stay subsequent to a challenge of an award, does not divest a party’s right to challenge, rather it only introduces minor changes to such an interim relief, which is not a vested or accrued substantive right.

JUDGMENT

On examining the contentions put forth by the parties and the contents of Section 26 of the Amendment Act, the Court came to a finding that the date of commencement of the Amending Act, that is, 23 October 2015, is what separates Section 26 into two parts: (i) the amendments shall not apply “to arbitral proceedings” commenced before the commencement of the Amendment Act, and (ii) the amendments shall apply “in relation to arbitral proceedings” commenced on or after the commencement of the Amendment Act.

The Court referred to the Thyssen judgment where the Supreme Court had observed that the right to enforce an award “when arbitral proceedings commenced under the old Act under that very Act was certainly an accrued right” and, “there is no necessity that legal proceedings must be pending when the new Act comes into force.” The Court construed this as equivalent to arbitral proceedings commenced prior to 23 October 2015, and an award being made prior to 23 October 2015 but challenge being made post-amendments, which is the present case.

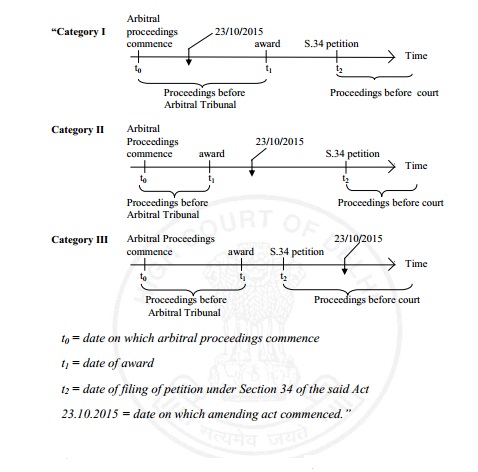

The Court accepted that the second part of Section 26 covers both, proceedings before the arbitral tribunal as well as court proceedings in relation thereto or connected therewith. However, the Court opined that if the applicability of the amendments to both parts are treated differently, it would lead to serious anomalies. This is primarily because of the fact that there have been amendments to Section 9 as well as Section 17 of Act8 and, in respect of arbitral proceedings commenced prior to 23 October 2015, the amended provisions would apply to proceedings under Section 9 of the Act, but not to Section 17 thereof. Thus, the expression “to arbitral proceedings” should be given the same expansive meaning as “in relation to arbitral proceedings” so that “all” arbitral proceedings (including court proceedings) that commenced prior to 23 October 2015 are governed by the un-amended provisions. To further illustrate all the arbitral proceedings, which commenced in accordance with the provisions of Section 21 of the Act prior to 23 October 2015, the Court referred to the following graphical representation:

Based on this representation, the Court concluded that if the first part of Section 26 applies only to arbitral proceedings in the sense of proceedings before arbitral tribunals and not to court proceedings, then, it is obvious that Section 26 is silent on second and third categories of cases. Thus, no contrary intention of retrospectivity could be inferred upon a reading of Section 26 of the Amending Act.

The Court, expanded the scope of the right to enforce an award as an accrued right to be inclusive of the negative right of the award-debtor to not have the award enforced. Thus, on considering that the right to have an automatic stay on the enforcement of the award has ceased, pursuant to the amendments, the Court concluded that these amendments are to be treated as prospective in operation.

ANALYSIS:

This judgment clearly conflicts with the earlier observations of the Madras High Court9 and the Calcutta High Court,10 wherein it was clarified that ‘arbitral proceedings’ do not include ‘court proceedings’ and by virtue of Section 26 of the Amendment Act, the amendments would apply to court proceedings but not to arbitral proceedings. Undoubtedly, these judgments rightfully establish the distinction between arbitral proceedings and proceedings emanating from or related to such arbitral proceedings as expressed in Section 26 of the Amendment Act, which has been diluted by the Court in this judgment.

The Bombay High Court11 looked into the intention behind the amendments and observed that the amendments to Section 36 sought to balance between the rights and liabilities of the award-holder and the award-debtor, thus prospective in nature. Earlier, a challenge under Section 34 would cast a shadow on the award-holder’s right to enforce the award since an automatic stay would operate. Subsequently, this shadow over the rights of the award-holder was removed, by way of the amendments. Meanwhile, the rights of the award-debtor were kept intact to the extent that interim reliefs can be sought from the court during the pendency of an application of challenge under Section 34. Thus, the Bombay High Court concluded that “removal of such a shadow over the rights of the award-holder cannot be said to be prejudicial to the award-holder.”

There is a risk of extension of ‘automatic stay principle’ which was prevalent in the pre-arbitration regime, debated and purposely omitted in the amendments to the Act. This judgment, if followed may defeat the intention of the amended Section 36 of the Act.

The decision of the Bombay High Court has been appealed and pending adjudication before Supreme Court of India. Hopefully, the Supreme Court will settle the position on applicability of the Amendment Act and bring the divergent views of various High Courts to an end.

– Shweta Sahu, Alipak Banerjee & Vyapak Desai

You can direct your queries or comments to the authors

1 Section 26 of the Amendment Act provides that: “Nothing contained in this Act shall apply to the arbitral proceedings commenced, in accordance with the provisions of section 21 of the principal Act, before the commencement of this Act unless the parties otherwise agree but this Act shall apply in relation to arbitral proceedings commenced on or after the date of commencement of this Act.”

2 New Tirupur Area Development Corporation Ltd. v. M/s. Hindustan Construction Co. Ltd A. NO. 7674 of 2016 in O.P. No. 931 of 2015 judgment dated 27 January 2016 (Madras High Court) [click here for our hotline]

3 Tufan Chatterjee v. Rangan Dhar AIR 2016 Cal 213

4 Rendezvous Sports World v. the Board of Control for Cricket in India, 2016 SCC Online Bom 255.

5 2017 SCC Online Del 6402

6 ibid

7 1999 (9) SCC 334.

8 Section 9 deals with the power of the court to grant interim measures, while Section 17 deals with powers of the arbitral tribunal to grant interim measures.

9 New Tirupur Area Development Corporation Ltd. v. M/s. Hindustan Construction Co. Ltd A. NO. 7674 of 2016 in O.P. No. 931 of 2015 judgment dated 27 January 2016 (Madras High Court)

10 Tufan Chatterjee v. Rangan Dhar AIR 2016 Cal 213

11 Rendezvous Sports World v. the Board of Control for Cricket in India, 2016 SCC Online Bom 255

Disclaimer

The contents of this hotline should not be construed as legal opinion. View detailed disclaimer.

Research PapersMergers & Acquisitions New Age of Franchising Life Sciences 2025 |

Research Articles |

AudioCCI’s Deal Value Test Securities Market Regulator’s Continued Quest Against “Unfiltered” Financial Advice Digital Lending - Part 1 - What's New with NBFC P2Ps |

NDA ConnectConnect with us at events, |

NDA Hotline |